CYBER THREAT INTELLIGENCE ARTICLE - A THREAT INTELLIGENCE ANALYST'S DIARIES

- About

-

Cloud Security

- About

- (ARTICLE) The ABC of Zero Trust and Interview with Cloud Leader “Swapnil Shah”

- (ARTICLE) SMEs are taking a Cloud-First approach, but are they prepared to handle cyber incidents?

- (ARTICLE) Importance of Clear Visibility through the cloud

- (ARTICLE) Securing Cloud Strategies

- (ARTICLE) Success in the Cloud: Three Commonsense Principles

- (ARTICLE) How HUAWEI Cloud Harness On Cloud Security

-

Cyber Threat

Intelligence

- About

- (ARTICLE) Introduction to the Blue Team

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (February Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (December Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (November Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (October Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (September Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (August Edition)

- (ARTICLE) Rantings of a Cyber Security Analyst - (July Edition)

- (ARTICLE) 2021 Malware and TTP Threat Landscape

- (ARTICLE) Mitigating Data Breaches and Protecting Personal Data

- (ARTICLE) Is Cyber Threat Intelligence necessary?

-

Data & Privacy

- About

- (ARTICLE) Understanding and Operationalizing Singapore’s Mandatory Data Breach Regime

- (ARTICLE) The Rising Concern of Data Privacy Around the World

- (ARTICLE) Protection Against Ransomware to Comply with Data Protection Law

- (ARTICLE) GDPR for Cybersecurity Practitioners

- (ARTICLE) Cybersecurity in the Protection of Personal Data

- Internet Of Things

A Threat Intelligence Analyst’s Diaries

Introduction

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) is not a new term and has been around for at least two decades according to the Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams (FIRST). However, in recent years the term has evolved significantly into a discipline. The reason behind this advancement can be attributed to the “Red Queen effect,” a coevolutionary hypothesis proposing that species must constantly adapt and evolve to survive against ever-evolving opposing species. Relating this hypothesis to cybersecurity, attackers and defenders are perpetually in a game of cat-and-mouse. In this game of “one-upmanship,” attackers devise novel tactics and techniques to bypass protections, prompting network defenders to implement stronger defensive measures, processes, and tools. As such, organizations have begun to establish new roles focused on CTI as part of their overall cybersecurity strategy.

In this article, I’ll share two key frameworks that are the “meat and potatoes” of CTI analysis and how they can be applied to a recent incident.

Cyber Kill Chain

Originally a military concept, the kill chain identifies the structure of an attack from the identification to the destruction of a target. It was later adapted by defense contractor Lockheed Martin to model computer network intrusions. The cyber kill chain follows these sequential phases:

1. Reconnaissance - The attacker first identifies their target, researches, and gathers information such as login credentials, network and operating system details, organization structure, etc.

2. Weaponization - Based on the intelligence gathered from previous phase, the attacker creates an attack vector to exploit known vulnerabilities on the target.

3. Delivery - The attacker then launches the attack typically via email or malicious website. In some cases, the attack might take place physically in the form of USB drives; for example, a USB Rubber Ducky.

4. Exploitation - The attacker attempts to exploit vulnerabilities on the target’s system.

5. Installation - Malware or other malicious payloads are installed on the target’s network or system.

6. Command and Control - To maintain persistence access to the target network, the attacker deploys a remote access tool like Cobalt Strike to connect remotely to the attacker-controlled infrastructure.

7. Actions on Objective - Finally, the attacker carries out their intended goal such as data exfiltration, destruction, or encryption.

Pyramid of Pain

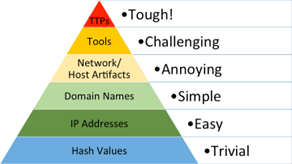

The Pyramid of Pain is a conceptual model created by David J. Bianco to illustrate the relationship between the type of indicators used to detect an adversary’s activities and the amount of pain inflicted on the adversary when it’s denied. The figure on the right shows the type of indicators organized within the pyramid according to their value and their level of detection and response. The pyramid’s exterior corresponds an indicator type with the amount of pain dealt to an adversary. At the base, hash values such as MD5, SHA1, and SHA256 are color-coded in blue representing the most accurate indicator type but causing a trivial amount of pain to an adversary. That’s because the adversary can effortlessly change the hash value of a malicious file just by changing a single bit. As defenders advance upward the pyramid, the color changes to green, yellow, and ultimately red, depicting the level of difficulty in terms of detection and response. Situated at the pyramid’s apex are an adversary’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) -- in other words, an adversary’s behavior or modus operandi. When defenders can detect and respond at this level, adversaries are compelled to adapt their operations entirely. This can be challenging because old habits are more difficult to change. I’d recommend reading David J. Bianco’s blog post that has greater details on the different levels of the Pyramid of Pain.

Case Study of the 3CX and TT Cascading Supply Chain Attack

On March 29, 2023, cybersecurity vendors CrowdStrike and SentinelOne reported an active supply chain attack hitting organizations using 3CXDesktopApp, a softphone application from video conferencing firm 3CX. , Three weeks later, 3CX released an update detailing findings from Mandiant’s investigation. Mandiant identified the initial compromise began in 2022 when a 3CX employee installed the Trading Technologies X_TRADER software on their personal computer. The trojanized software led to the deployment of VEILEDSIGNAL malware that enabled the suspected North Korean threat actor (UNC4736) to initially compromise and maintain persistence on the employee’s personal computer.

With reference to Mandiant’s report, I applied the two aforementioned frameworks in this case study as follows:

Cyber Kill ChainReconnaissance - Considering the attack path, it appears that UNC4736 has initially identified Trading Technologies as their target.

Weaponization - In November 2021, UNC4736 used a legitimate digital certificate to sign a trojanized version of X_TRADER.

Delivery - Prior to August 2022, the 3CX employee downloaded the trojanized software to their personal computer.

Exploitation - UNC4736 was able to gain elevated access to the 3CX employee’s personal computer and subsequently harvested their 3CX work credentials.

Installation - The installation of trojanized X_TRADER software led to the deployment of VEILEDSIGNAL backdoor.

Command and Control - VEILEDSIGNAL contains a C2 (command and control) module used to beacon to UNC4736’s controlled infrastructure.

Actions on Objective - Due to ongoing investigations, it remains unknown what the intended goals of UNC4736 are.

Pyramid of PainA complete list of indicators of compromise (IOCs) can be found on Mandiant’s blog.

- TTPs - Refer to the Technical Annex in Mandiant's Blog

- Tools - Fast Reverse Proxy (frp) used for lateral movement

- Network/Host Artifacts - VEILEDSIGNAL backdoor

- Domain Names - www[.]tradingtechnologies[.]com

- IP Addresses - 52[.]1[.]242[.]46 (Note the IP in question might not necessarily be malicious as it could resolve to other domains)

- Hash Values - MD5: ef4ab22e565684424b4142b1294f1f4d (X_TRADER_r7.17.90p608.exe)

References:

- https://www.first.org/global/sigs/cti/curriculum/cti-introduction

- https://www.lockheedmartin.com/content/dam/lockheed-martin/rms/documents/cyber/Gaining_the_Advantage_Cyber_Kill_Chain.pdf

- http://detect-respond.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-pyramid-of-pain.html

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/crowdstrike-detects-and-prevents-active-intrusion-campaign-targeting-3cxdesktopapp-customers/

- https://www.sentinelone.com/blog/smoothoperator-ongoing-campaign-trojanizes-3cx-software-in-software-supply-chain-attack/

- https://www.3cx.com/blog/news/mandiant-security-update2/

- https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/3cx-software-supply-chain-compromise

- https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/3cx-software-supply-chain-compromise

Author Bio

Jeremy Ang

Jeremy is an information security professional with a decade of experience in the financial services, pharmaceutical and MSSP industries. He has a bachelor’s degree in computer science and holds various industry certifications including CISSP, GCFA, GREM, GDAT, GCTI, GMON, and GCIH. Jeremy is a member of AiSP Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) Special Interest Group (SIG) and currently a Senior Threat Intelligence Analyst with Intercontinental Exchange, Inc., a Fortune 500 company that designs, builds and operates digital networks to connect people to opportunity.

Any views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the author’s employer.